If you’ve arrived here from a search engine or just clicked on the article link, we recommend reading this article first. It will enable you to form a better understanding of maternal and infant mortality globally and how the issue is indicative of a larger set of biases that pervade healthcare.

This article focuses on Clinics IV Life and the model we have developed to address these issues in disadvantaged communities. If you want to understand exactly what it is we do and how we do it, this article will shed light. As to the “why” it is so essential, refer to the piece linked above.

Throwing money at a problem

A lot of the aid that is extended to needy communities is often as a result or aftermath of a destructive storm, famines, floods, earthquakes and typhoons. While this help is critical and save lives, the issue of addressing long term challenges faced by disadvantaged communities often goes unaddressed. Money is a quick and easy fix for the first world. It alleviates our collective conscience and we can move on, leaving the indigent communities we’ve just “saved” to their own lots.

This is especially true of healthcare and sadly, much of what is done in remote rural locations is done with an underlying agenda, be it political, economic or simply recruiting future cohorts for clinical trials. Good, performed with an agenda, always comes at a price. These actors also detract from the real good done by amazing charities, like Save the Children, that operate selflessly for the good of the communities they serve.

Clinics IV Life wanted to develop projects that could immediately impact the health outcomes in the areas we identified. Projects that were sustainable over time and that would eventually, become self sustained. The question was, how?

Building for better health

Having extensive exposure to indigent communities in Asia, we decided to launch our pilot projects in rural areas of the Philippines. To offer an effective, long term solution to maternal and infant health in these areas, we needed to establish a lasting physical presence and nothing shouts “we’ve arrived” louder than a building. We opted for purchasing tracts of ground and constructing two floor clinics in areas of special need (ASN’s) we had identified.

The clinics function in the following way. We engage the services of a local OBGYN and a Pediatrician for each clinic. These healthcare specialists are contracted on a full time basis to a specific clinic with a Shared Practice Agreement (SPA). The SPA enables them to run a thriving practice from a fully equipped clinic in exchange for providing an agreed number of consultations per week for indigent mothers. Our goal for each clinic is reaching 1000 mothers a year.

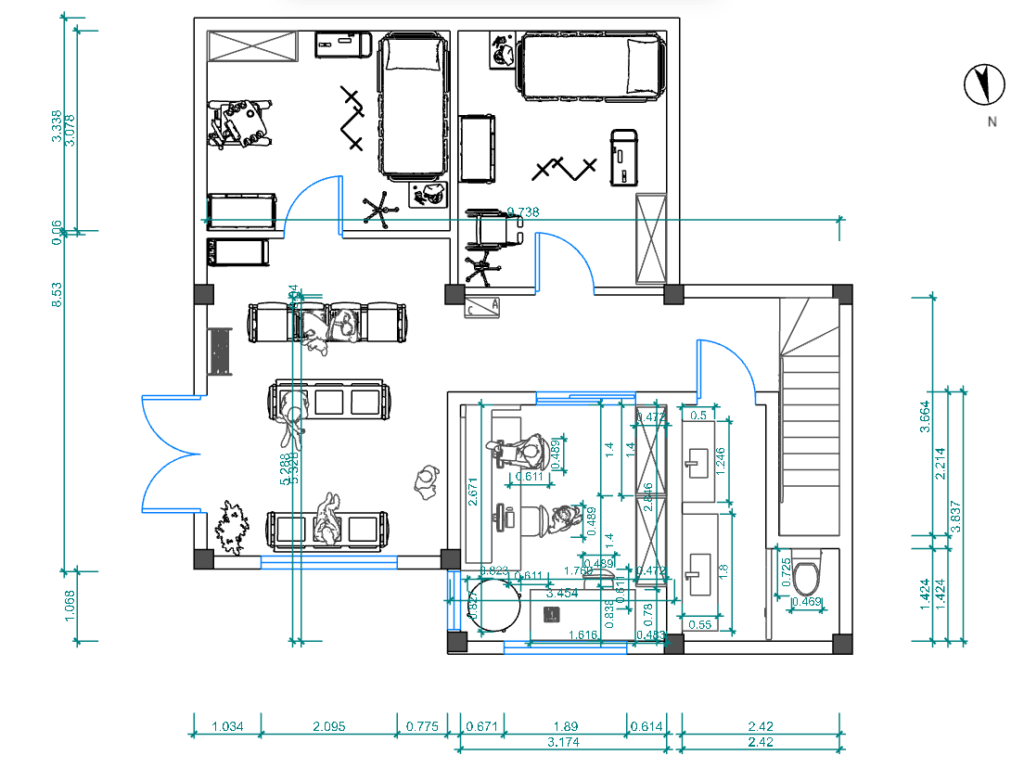

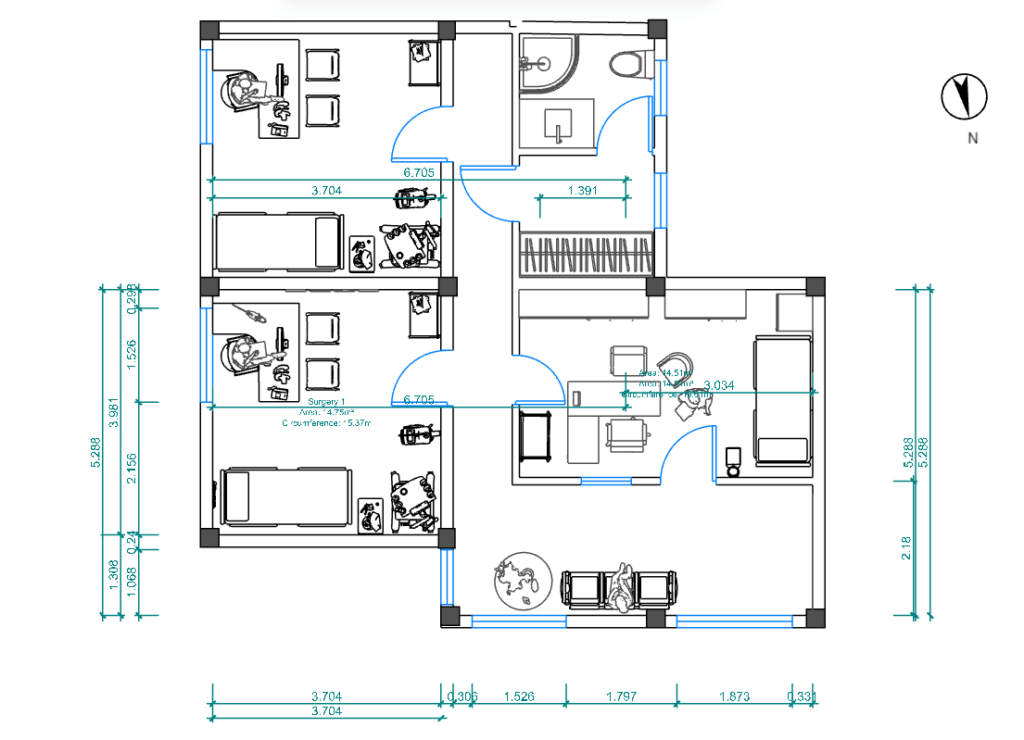

Our clinics follow a predesigned format to reduce cost with subsequent builds (formwork, architect fees, etc.) and offer two individual consulting suites, a nurses station and two dedicated birthing rooms. The layouts shown below are typical and only vary slightly to accommodate location.

The communities we serve are engaged from the outset, with local builders and skills utilized for construction. We consult with local council driven health initiatives and ensure these bodies understand we are merely providing ancillary services, otherwise unavailable, to supplement their care.

Decentralized Care

There are numerous factors contributing to the abysmal levels of care disadvantaged communities have historically been exposed to. In many ways, healthcare itself is to blame, particularly true in more developed countries were prohibitive and extortionate pricing control and blatant profiteering drive up the cost of care. For poor communities, in countries like America, access has nothing to do with a lack of services and everything to do with simple economics. These communities can no longer afford care. They have been priced out of healthcare.

Our clinic model seeks to address this by severing some of the mechanisms that drive up prices. Providers, for instance, that are not joined at the hip to healthcare insurers and dictated, expensive medications, can afford to spend more time engaging with patients, forming proper diagnosis and offering real levels of care.

In poorer third world countries, doctors very often do not have the funds to adequately equip private practices, an issue that seriously hampers their ability to deliver adequate levels of care. We remove this obstacle by providing the security of a free, fixed place of practice and access to fully equipped surgeries, leaving the medical professional free to ply their trade and focus on the wellbeing of their patients.

Flexibility is a key element of change

Any system that is inflexible is unsuited for the dynamic field of medicine. There simply are no “one solution fits all” answers to the ills and biases that plague modern healthcare. It is a hugely complex industry and subject to the whims of both politics and profit, in equal measure. This complexity is possibly the largest deterrent to change.

Our model is simple, provides immediate benefit with construction taking a few months, and relies on only a few key elements that can be adjusted to best “fit” the countries we deploy it in. It is this flexibility we believe make the model viable across other sectors of health that deal with other specialties and we welcome enquiries from any sector seeking to expand care to disadvantaged communities.